WINDRUSH FOOD CULTURE

FROM THE MARGINS TO THE MAINSTREAM.

Recognition, Revolution and the Flavours of Belonging. A Story of Survival, Belonging and Joy — Told Through Taste

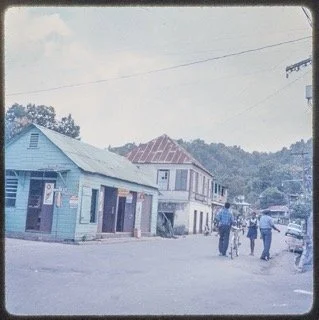

The Original Caribbeans Before the Ship — The Caribbean Kitchen Begins

Roots

Coming to Britain — Recipes, Seeds and Memory

Arrival

Making a Life

Markets, Windrush Women, Kitchens — Building Through Food

Taking to

the Streets

From Jerk Pans to Carnival Stalls — Food as Culture

From the

Margins to the

Mainstream

Recognition, Revolution and the Flavours of Belonging

Food is power

Memory Passed Through Hands. History Served on a Plate.

Windrush Kitchen

& Dining Room

The Heart of the Home

TASTE MAKERS

Windrush Chefs, Food Entrepreneurs & Icons.

Food was one of the first languages of Windrush Britain. In cafés, church halls, takeaways and television studios, Caribbean cooks and culinary leaders turned family flavour into public culture — and into business.

They turned patties and pepper sauce into stories of pride, resilience, and economic power.

Featured Icons:

• Rustie Lee — Pioneer of Flavour & Laughter

• Wade Lyn CBE — Island Delight Patties

• Levi Roots — The Sauce That Sang a Nation

• Michael Caines MBE is a renowned Michelin-starred British chef and restaurateur

• Andi Oliver — Chef, Broadcaster, Curator

• Ainsley Harriott — TV’s Caribbean Comfort King

• Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones — The Black Farmer

• Lorraine Pascale — Elegance in Every Bake

• Caribbean Takeaway Legends — The High Street Heroes

• Jerk Pan Masters & Carnival Cooks — Street-Level Innovators

• Windrush Elders (Grandmas’ hands)

• Future Plate -a collective of leading Black chefs and culinary creatives celebrating African and Caribbean cuisine through immersive dining experiences, cultural storytelling, and high-profile collaborations including Julian George (founder), Jason Howard, Opeoluwa “Opy” Odutayo, William Chilia, and Daniel Rampat.

• Ryan Matheson is a Jamaican-born chef with over 25 years of experience who now serves as an Executive Chef.